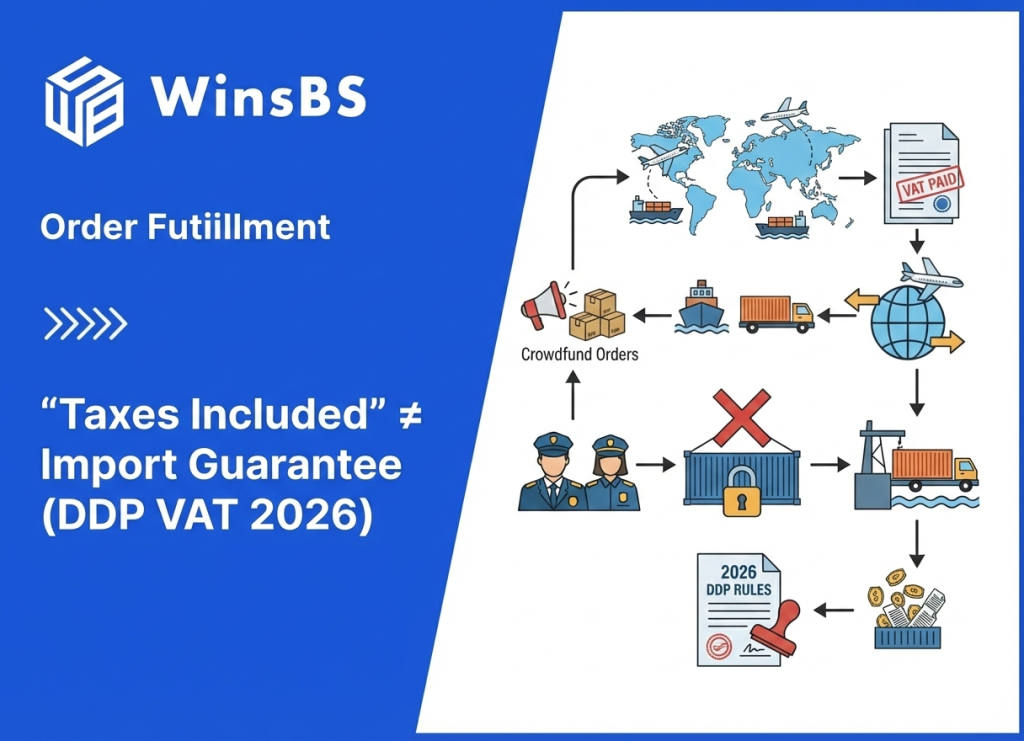

“Taxes Included” ≠ Import Guarantee (DDP VAT 2026)

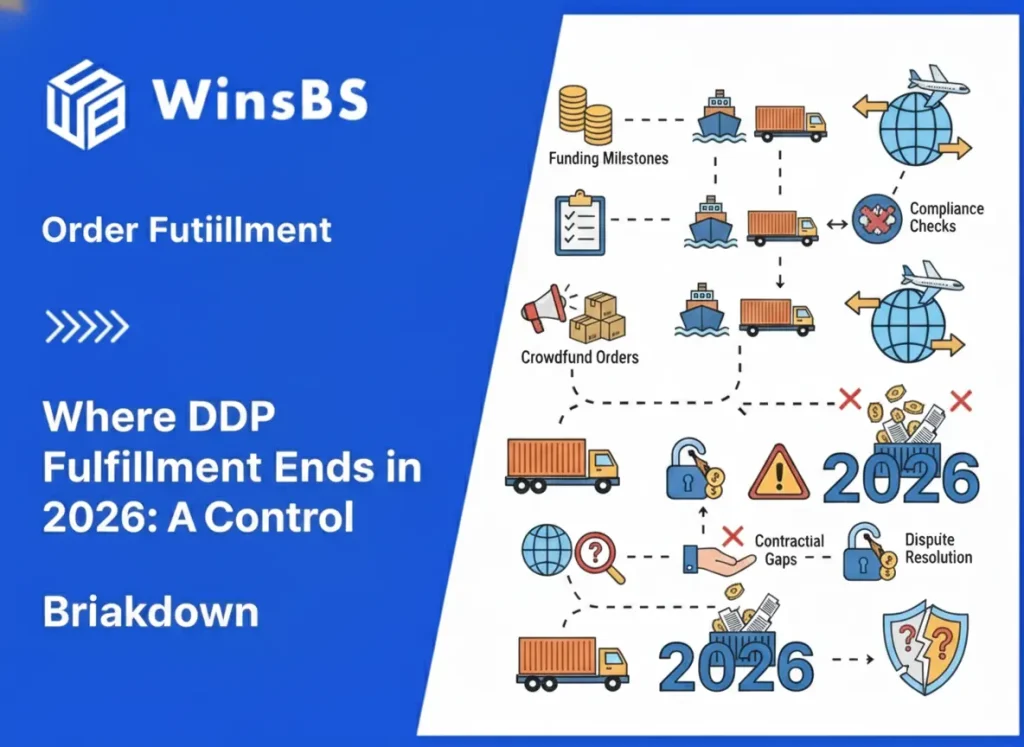

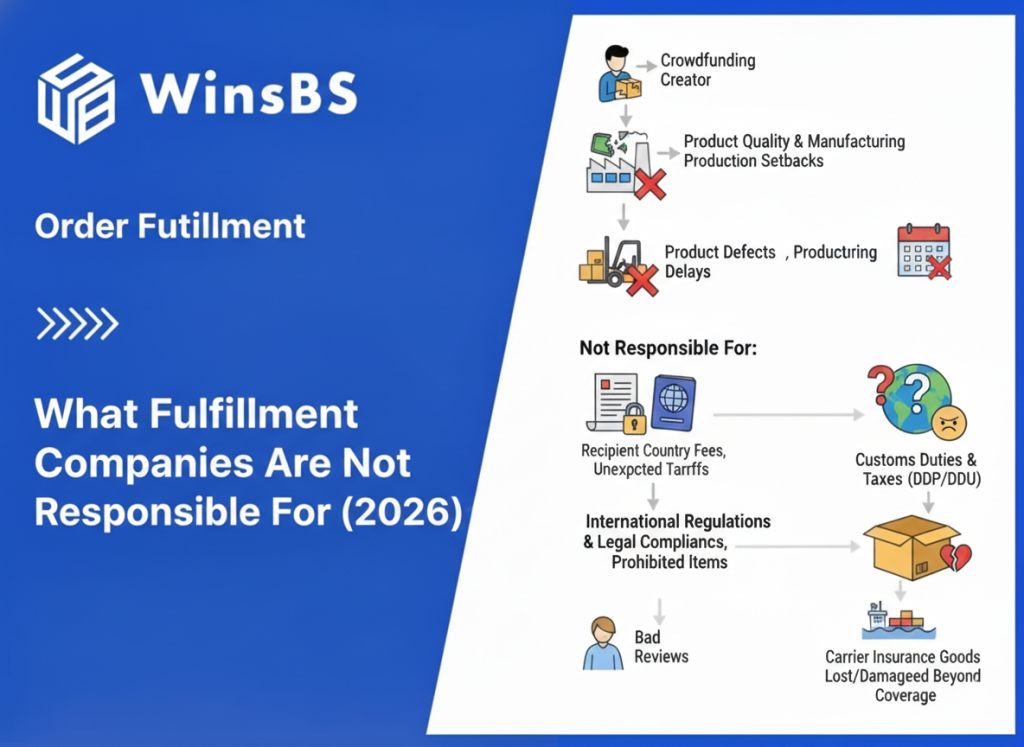

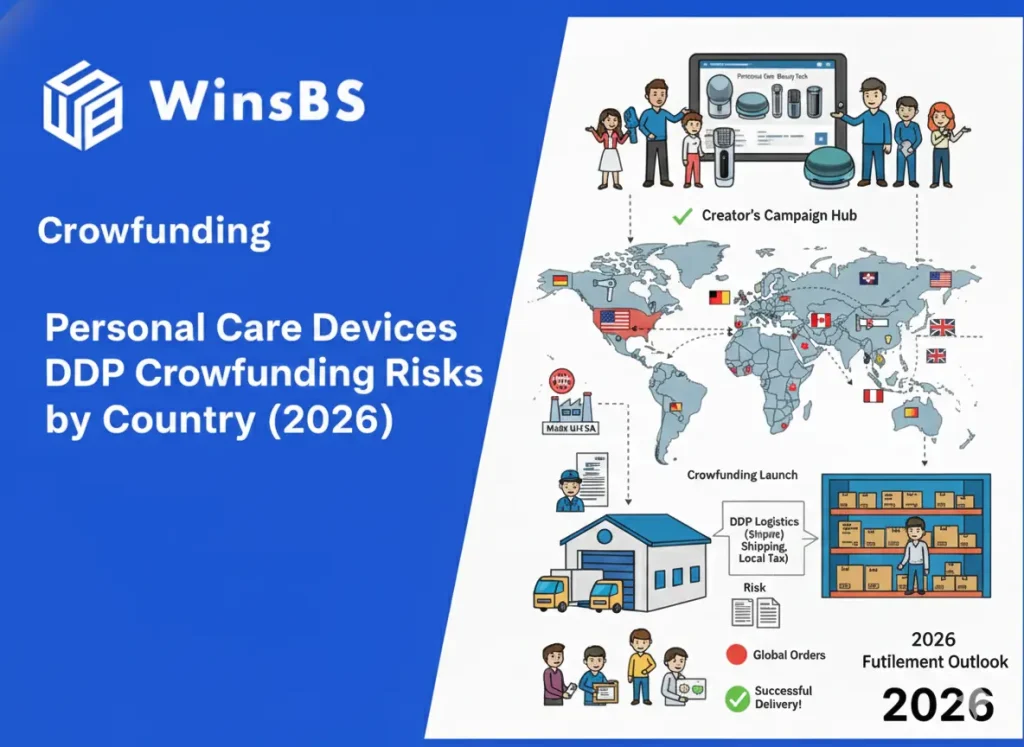

“Taxes Included” ≠ Import Guarantee (DDP VAT 2026) Why VAT & GST Get Recalculated at EU, UK & Canada Borders WinsBS Fulfillment — Maxwell Anderson Updated February 2026 · Cross-Border DDP · VAT / GST · Customs Validation Positioning note: This article builds on the execution boundaries explained in Order Fulfillment in 2026: What It Includes & Where It Stops , What Fulfillment Companies Are Not Responsible For (2026) , and Where DDP Fulfillment Ends . It documents a repeatable cross-border scenario in 2026: VAT or GST is collected at checkout — yet import tax is requested again at entry in the EU, UK, or Canada. Contents 0. The Parcel Arrived. The Tax Bill Arrived Too. 1. The Order That Looked Fully Settled 2. Where the Recalculation Actually Begins 3. Why the 3PL Cannot Repair This Stage 4. Route Differences: EU, UK, Canada, US 5. 2026 Confirmed Validation Variables 6. When the Buyer Says, “But I Already Paid” 0. The Parcel Arrived. The Tax Bill Arrived Too. The shipment was sent under DDP. At checkout, your buyer saw “taxes included.” The order total already reflected VAT or GST. No additional fee was expected at delivery. The warehouse packed the order. A label was generated. Tracking went live. For several days, everything moved normally. Then one of two things happened. If the parcel was entering the UK, Royal Mail sent a payment request before delivery. If it entered Canada, the courier issued a GST collection notice. If it entered parts of the EU, the parcel paused in customs with VAT under review. The buyer forwarded the message to you. “I thought tax was included.” From your side, it was. The dashboard shows prepaid shipping. The invoice shows tax collected. Nothing is marked unpaid. But the import system is not looking at your checkout page. It is evaluating the parcel as it enters the country. This is the moment where the logic breaks: You paid the tax at sale. The import system is calculating tax at entry. Both are real. They are not the same system. This article starts from that split. 1. The Order That Looked Fully Settled The order was simple. A €120 skincare device shipped from Shenzhen to Germany under a DDP cross-border fulfillment structure. VAT was calculated at checkout. The buyer paid €142.80 in total, including 19% VAT. On your dashboard, the order showed: Product value: €120 VAT collected at checkout: €22.80 Shipping: prepaid (DDP) Status: paid The fulfillment system received that order exactly as shown. The warehouse picked the unit. A DDP shipping label was generated. Electronic customs declaration data was transmitted with: Declared value: €120 HS code attached for EU import classification Sender: your entity Importer: auto-assigned under the shipping structure The parcel left the warehouse. Up to this point, every number matched. The VAT collected at checkout matched the invoice. The invoice matched the shipment record. Nothing was missing from the fulfillment side. Three days later, the parcel reached the EU entry point. Now the EU import system evaluated the parcel independently as an import declaration, not as a checkout transaction. It did not look at the Shopify checkout page. It did not see the buyer-facing “tax included” confirmation. It evaluated: Is there a valid VAT or IOSS linkage inside the entry data? Does the importer registration match the declared responsible party? Is the declared goods value consistent with EU entry thresholds? If any of those elements do not reconcile inside that customs validation system, the parcel is treated as taxable at entry — regardless of what was paid at sale. That is the split. At checkout, VAT was a pricing component. At EU border entry, VAT becomes a compliance validation event. Those two events reference the same amount. They do not share the same verification logic. And that structural separation between checkout tax collection and import tax validation only becomes visible when the parcel reaches the border. 2. Where the Recalculation Actually Begins Three days after dispatch, the parcel reaches the EU entry hub. At that moment, the shipment is no longer treated as an order. It is treated as an import declaration under EU customs validation. The system now checks whether the VAT that was collected at sale is properly linked inside the electronic entry data. For the €120 device shipped from China to Germany, one of four recurring validation triggers typically initiates re-evaluation. 1) VAT or IOSS linkage mismatch If an IOSS number was used for EU VAT-at-sale collection, it must be correctly attached to the customs declaration and match the declared goods value. If the number is missing, expired, misformatted, or not recognized inside the EU import dataset, the system does not assume VAT was paid at checkout. It calculates VAT again at entry. 2) Importer identity inconsistency The checkout invoice lists your company as seller. The EU entry declaration may list a different acting importer depending on the DDP routing structure. If those identities do not reconcile inside the customs validation system, VAT is not considered validated. The parcel pauses for tax assessment. 3) Value structure difference between sale and entry Checkout total: €142.80 (goods + VAT). Declared import value: €120 (goods only). The EU customs system evaluates the declared goods value, not the buyer-facing checkout total. If VAT linkage does not successfully validate against that declared value, VAT is recalculated against €120 at entry. 4) Multi-parcel split creating independent entry records If the shipment was operationally split into two parcels for routing efficiency, each parcel is evaluated independently at EU entry. If one parcel crosses a validation threshold differently, or loses IOSS linkage in data transmission, it may fall outside the prepaid VAT structure. One parcel clears normally. The other enters VAT reassessment. At this stage, the EU import system is not “charging twice.” It is performing its own tax validation cycle based on the customs declaration record. And once that validation cycle begins, the checkout record is no longer relevant to the import decision. In standard cross-border