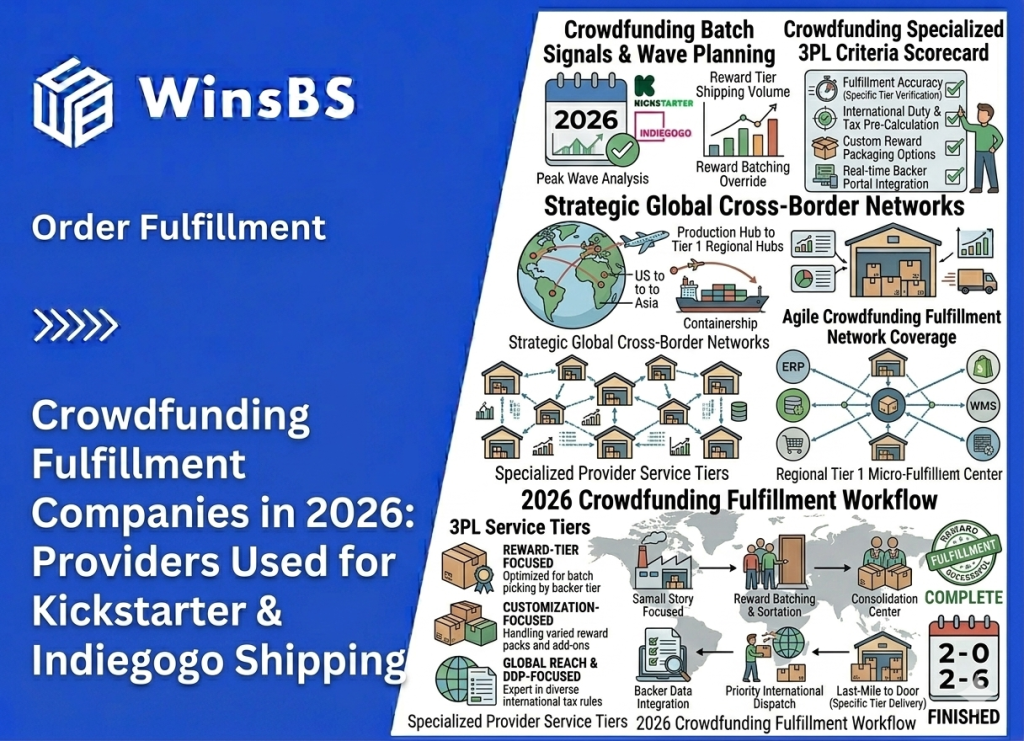

Crowdfunding Fulfillment Companies in 2026: Providers Used for Kickstarter & Indiegogo Shipping

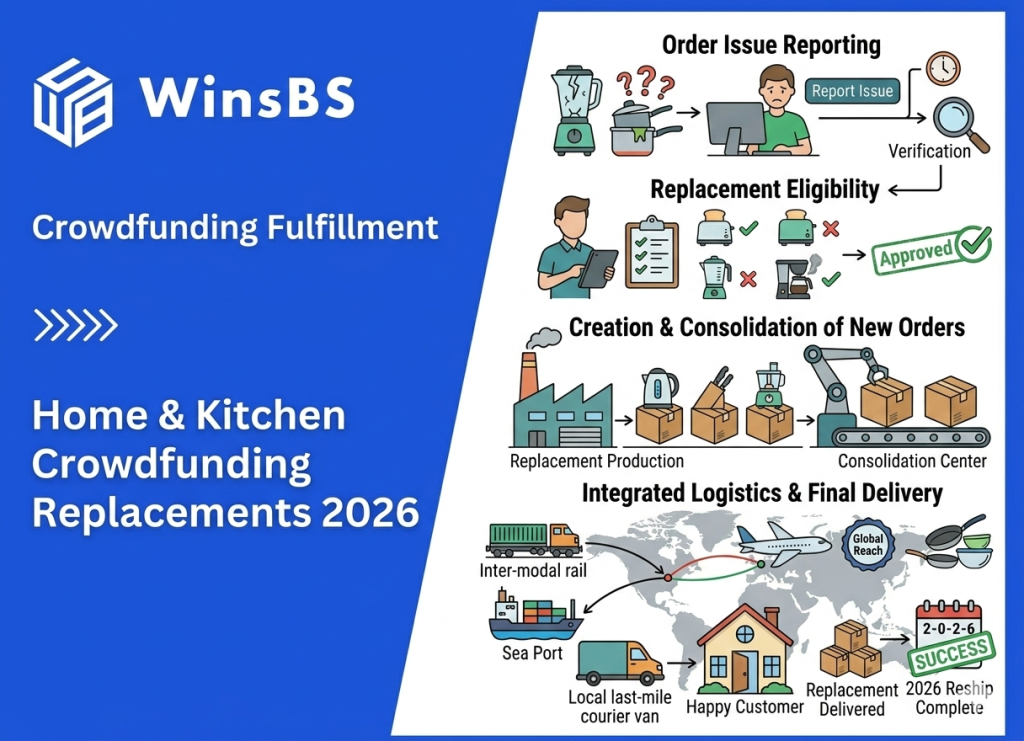

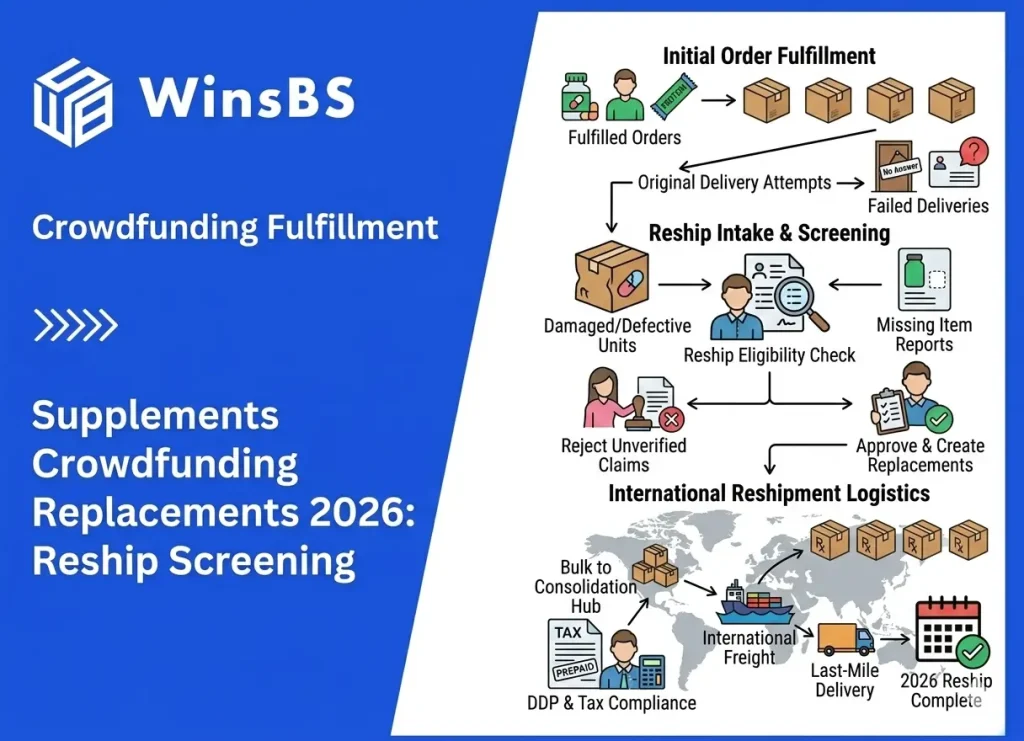

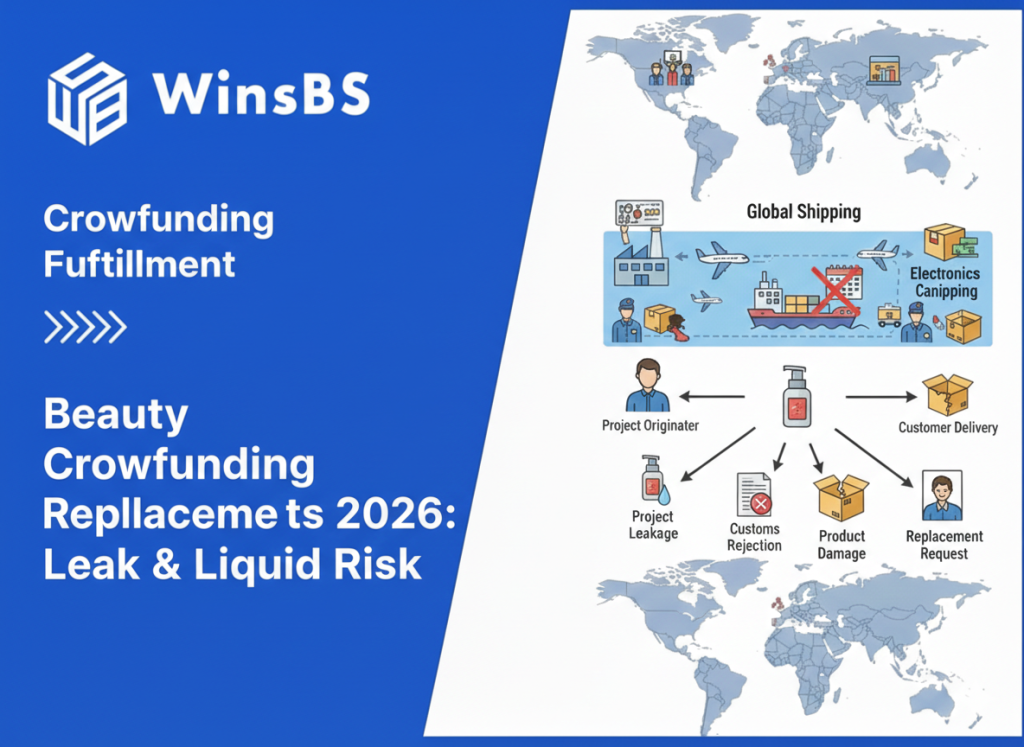

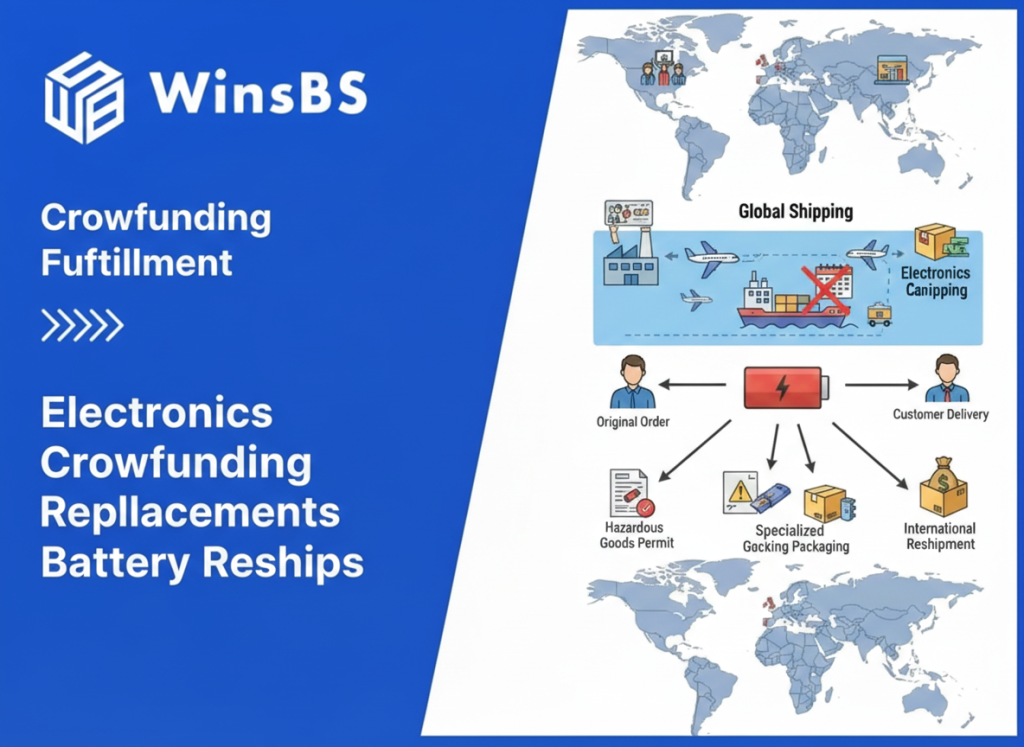

Crowdfunding Fulfillment Companies in 2026: How Campaign Creators Handle Reward Shipping and Global Backers Maxwell Anderson Independent 3PL Research March 2026 TLDR Crowdfunding campaigns rarely ship like a normal ecommerce store. Rewards may change after funding, inventory often arrives in stages, and backers can be spread across dozens of countries. Because of this, creators usually work with fulfillment providers that can handle bundle assembly, staged shipping waves, and international reward delivery. This guide summarizes crowdfunding fulfillment companies frequently considered in 2026 and focuses on operational signals rather than rankings, so creators can judge which workflows fit their campaign once funding closes and shipping begins. This page is part of the 2026 Ecommerce 3PL Signal Index, where crowdfunding fulfillment is analyzed as one execution category within the broader 3PL ecosystem. Contents Quick Answers About Crowdfunding Fulfillment Crowdfunding Fulfillment Providers Frequently Used by Campaign Creators Operational Patterns Observed in Crowdfunding Fulfillment Execution Capabilities Required for Campaign Fulfillment Crowdfunding Fulfillment Execution Signals Dataset When Crowdfunding Campaigns Require Specialized Fulfillment Operational Risk Signals in Campaign Fulfillment Crowdfunding Fulfillment Within the 3PL Execution Landscape Observation Sources and Signal Methodology Editorial Independence Quick Answers About Crowdfunding Fulfillment Quick Answer Quick Answer What is crowdfunding fulfillment? Crowdfunding fulfillment refers to the logistics process of shipping campaign rewards to backers after funding closes. Instead of handling a stable retail order flow, campaign logistics often involve reward bundles, survey data, staged inventory arrivals, and international reward shipping. Quick Answer How is crowdfunding fulfillment different from ecommerce fulfillment? Crowdfunding fulfillment usually begins after funding closes, not at the moment an order is placed, and reward structures may continue changing before shipment. This makes campaign fulfillment more dependent on bundle assembly, staged shipping, and exception handling than standard ecommerce order processing. Quick Answer Why do crowdfunding campaigns often ship in multiple waves? Crowdfunding campaigns often ship in multiple waves because manufacturing completion, inventory arrivals, and regional shipping readiness do not always align at the same time. Multi-wave shipping is a common campaign logistics pattern rather than an unusual exception. Quick Answer What capabilities matter most in crowdfunding fulfillment? The most important capabilities usually include reward bundle kitting, staged shipping coordination, address update handling, replacement logistics, and international shipment management. These capabilities matter because campaign fulfillment rarely follows a fixed one-order, one-SKU workflow. Crowdfunding Fulfillment Providers Frequently Used by Campaign Creators Once a crowdfunding campaign reaches its funding goal, the next problem is no longer fundraising — it is fulfillment. Creators need to ship rewards to hundreds or thousands of backers, often across multiple countries, while dealing with bundle variations, staged inventory arrivals, and changing shipping data. Because of this, creators comparing crowdfunding fulfillment companies usually care less about generic service claims and more about operational fit. The providers below appear frequently in campaign logistics discussions because their workflows align with recurring crowdfunding shipping patterns rather than a single universal “best” setup. Campaign Fulfillment WinsBS Typical Campaign Fit: Projects with complex reward bundles, staged shipping waves, creator-side variability, and a need for hands-on coordination during campaign fulfillment. Operational Signals: Bundle kitting workflows, campaign logistics coordination, replacement shipment handling, and fulfillment support for changing reward structures. Reward Fulfillment Fulfillrite Typical Campaign Fit: Small-to-mid-sized crowdfunding campaigns with relatively stable reward structures and a need for recognized campaign fulfillment experience. Operational Signals: Reward shipping familiarity, campaign creator visibility, and recurring mention in Kickstarter and Indiegogo fulfillment conversations. Scaling DTC ShipBob Typical Campaign Fit: Campaigns that expect to move from initial reward fulfillment into ongoing ecommerce operations after launch. Operational Signals: Distributed warehouse network, platform integrations, and stronger fit where crowdfunding transitions into repeat DTC order flow. Omnichannel Operations ShipMonk Typical Campaign Fit: Campaigns that need broader ecommerce infrastructure alongside reward shipping, especially when long-term channel expansion matters. Operational Signals: Omnichannel workflows, platform integration support, and operational fit for brands building beyond the initial campaign stage. Heavy / High-Value Products Red Stag Fulfillment Typical Campaign Fit: Hardware-focused or oversized reward campaigns where product weight, fragility, or value creates more handling pressure than normal parcel fulfillment. Operational Signals: Reputation for careful handling, high-value shipment focus, and stronger alignment with campaigns built around heavier physical rewards. Provider Best Fit Execution Signal WinsBS Complex campaign logistics Bundle kitting, staged shipping, campaign coordination Fulfillrite Small-to-mid campaign fulfillment Reward shipping familiarity and creator adoption ShipBob Campaign-to-DTC transition Distributed fulfillment and ecommerce integration ShipMonk Omnichannel post-campaign growth Broader platform operations and channel support Red Stag Fulfillment Heavy or high-value reward products Careful handling and product-specific fulfillment fit The shortlist above is meant to help campaign creators orient quickly before moving deeper into execution patterns. Crowdfunding fulfillment companies tend to differ less on generic “service quality” language and more on whether their workflows match reward shipping, bundle assembly, staged inventory releases, and international backer handling. Operational Patterns Observed in Crowdfunding Fulfillment At first glance, shipping rewards from a crowdfunding campaign may seem similar to shipping ecommerce orders. In practice, the logistics structure is usually different. Reward bundles may change after funding, inventory may arrive from multiple suppliers, and backers may be spread across many countries before a final shipping plan is fully locked. These conditions create recurring fulfillment patterns that campaign creators run into again and again once funding closes. They show up in shipping timelines, creator updates, and campaign logistics discussions long before the first rewards leave the warehouse. Reward Bundle Expansion After Funding Crowdfunding campaigns frequently begin with a limited set of reward tiers, but the number of items included in those rewards often expands during the campaign. Stretch goals, add-ons, and upgraded pledge tiers can gradually change what must actually be packed and shipped. Observation: Reward bundles in crowdfunding campaigns often expand between the early campaign phase and final fulfillment. Explanation: Stretch goals and optional add-ons frequently introduce additional products into the final reward structure. Implication: Fulfillment operations must support flexible bundle kitting rather than a fixed SKU-per-order workflow. This is one of the main reasons campaign fulfillment rarely follows the same pick-and-pack workflow used in traditional ecommerce operations.