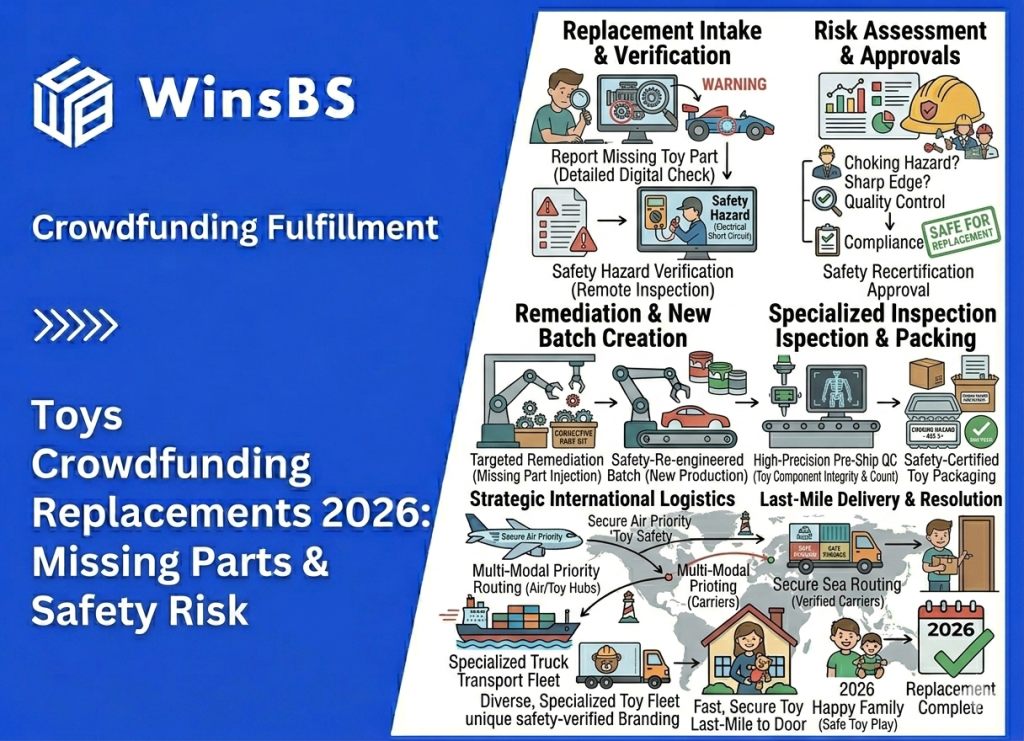

Toys Crowdfunding Replacements 2026: Missing Parts & Safety Risk

Toys Crowdfunding Replacements in 2026 Why “missing parts” turn into safety perception, component stockouts, and long-tail reships WinsBS Fulfillment — Maxwell Anderson Updated February 2026 · Toys & Kids · Crowdfunding Fulfillment · Reship & Replacement TL;DR: In toys crowdfunding, replacement tickets rarely stay “one-off.” A missing accessory, small part, or wrong variant can quickly turn into a trust problem: parents ask whether the product is safe, complete, and consistent. The second cycle stays open when you still have inventory — but not the exact parts needed to close cases cleanly. On this page You Delivered the Toys — Then the “Missing Piece” Messages Start The Toy Replacement Problem Is Usually Component-Level, Not Unit-Level Why Safety Perception Changes the Tone of Replacements Packaging & Kitting Drift: How “Complete Sets” Become Inconsistent Variant Confusion: Age, Language, and Regional Differences Returns Don’t Rebalance Toys the Way You Expect What Actually Closes a Toys Replacement Cycle Methodology & Sources You Delivered the Toys — Then the “Missing Piece” Messages Start The main wave looks clean. Parcels arrive, tracking turns Delivered, and photos start showing up in comments. For a toy campaign, that public unboxing moment matters — because your buyers aren’t only buyers. Many are parents, gift-givers, and first-time backers watching each other’s experiences. Then the first ticket hits — and it rarely sounds like “damage.” “The set is missing one small piece.” “We didn’t get the accessory shown in the update.” “It arrived, but the bag inside looks opened.” “Is this safe? There are loose parts in the box.” “Another backer got a different version — why?” At first this feels minor. One missing token. One accessory. One small part that fell out of a bag. In toys, “missing parts” are not just completeness issues. They become trust issues — especially when kids are involved. A backer missing a board game card is annoyed. A parent missing a small toy part immediately thinks about choking hazard, QC, and whether the product was handled correctly. The ticket tone changes. This is why toy replacements behave differently from many categories: the underlying issue might be small, but the perceived risk is large. And perception spreads faster than your support queue can close cases. If you shipped 5,000 units, even a quiet 0.5% “missing component” rate is 25 cases — enough to create a visible thread if cases cluster around one batch, one fulfillment lane, or one pack-out step. The first cycle delivers toys. The second cycle proves the sets are complete and consistent. The Toy Replacement Problem Is Usually Component-Level, Not Unit-Level In many crowdfunding categories, replacements happen at the unit level. A garment is swapped. A device is replaced. A bottle is resent. Toys rarely behave that way. Most tickets are not: “The entire product is unusable.” They are: One connector piece is missing. A small molded part cracked. A sticker sheet was left out. An accessory pack is incomplete. The wrong color variant was inserted. That distinction matters operationally. Toy replacement stress concentrates at the component level, not the finished-unit level. Your WMS may show 800 finished units remaining. That looks safe. But if 40 replacement tickets all request the same small part — and you only packed 50 spare pieces — your effective replacement capacity collapses immediately. Unlike apparel, where size imbalance drives the second cycle, toy campaigns often stall because one specific component: was under-packed as spare stock, was sourced from a slightly different batch, or has a slightly higher break rate than forecast. Once that component buffer runs thin, every new ticket feels heavier. Replacement cycles in toys stall when the spare-part pool drains — even if full boxed inventory still exists. Some creators respond by sending entire replacement units instead of individual parts. That closes tickets faster, but it accelerates finished inventory depletion. Over time, this creates a quiet shift: Spare components run out. Whole units are shipped as replacements. Replacement volume begins to exceed original defect assumptions. What started as a “missing piece” issue becomes an inventory reallocation issue. In toy crowdfunding, the second cycle is controlled by the smallest part in the box — not by the box itself. Missing Component (The “Small Part” Problem) Public Visibility Safety Concerns Spike Ticket Volume ×4 Full Unit Cannibalization Secondary Cycle Crisis WinsBS Inventory Depletion Logic Why Safety Perception Changes the Tone of Replacements A missing accessory in an adult product is an inconvenience. A missing or loose part in a children’s product feels different. The language in support tickets shifts quickly: “Is this a choking hazard?” “Was this inspected before shipping?” “Are other sets affected?” “Should we stop letting our child use it?” At this point, the issue is no longer about logistics. It becomes about perceived product safety and quality control. In toy crowdfunding, perception escalates faster than defect rates. Even if the actual failure rate is low, once a few similar cases appear publicly — in campaign comments, Facebook groups, or Reddit threads — more backers begin inspecting their sets more closely. That inspection effect increases ticket volume. Not because the defect suddenly spread, but because visibility increased. Visibility multiplies replacement demand. This dynamic is specific to crowdfunding. Retail environments diffuse complaints across channels. Crowdfunding concentrates them in one public place. When multiple backers reference the same missing part in a visible thread, others who might have ignored a minor issue now submit a ticket. The replacement cycle extends — not purely from operational failure, but from heightened scrutiny. In toys, the second cycle is shaped as much by public attention as by physical defects. That is why toy replacement curves often show a spike several days after the first public comment, rather than immediately after delivery. Packaging & Kitting Drift: How “Complete Sets” Become Inconsistent Most toy crowdfunding campaigns rely on kitting. Multiple small components are packed together: molded parts, accessory bags, instruction sheets, stickers, inserts, sometimes across more than one assembly line or fulfillment batch. During the main wave, everything appears standardized. Boxes