When Inventory Exists but Delivery Is Impossible in 2026 | Cross-Border Fulfillment

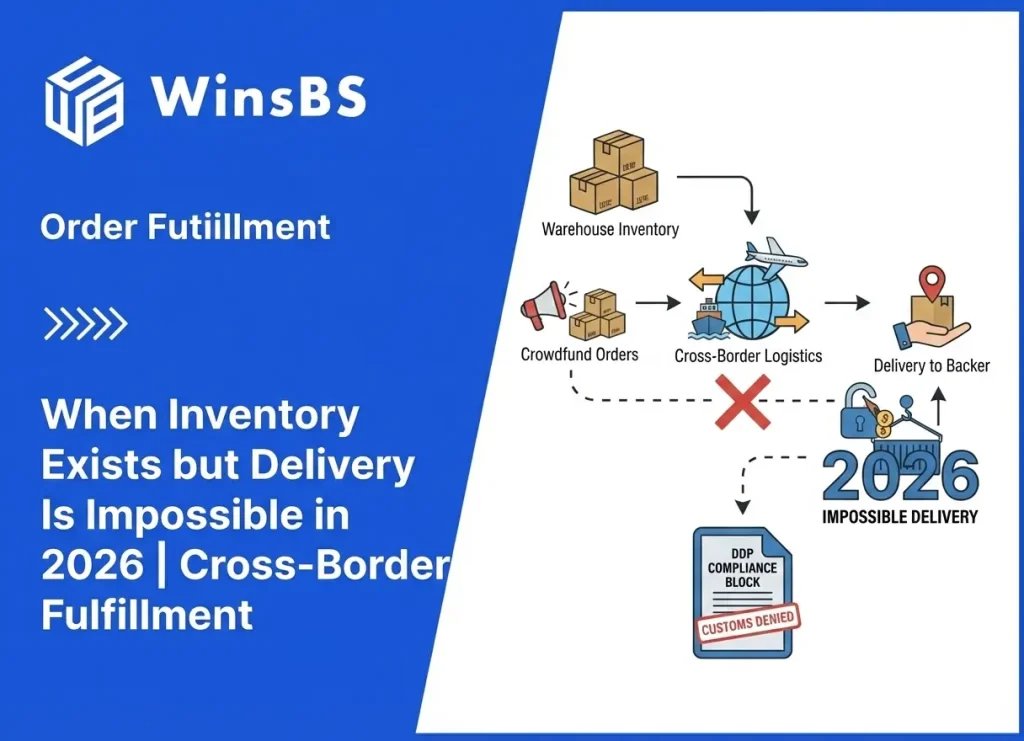

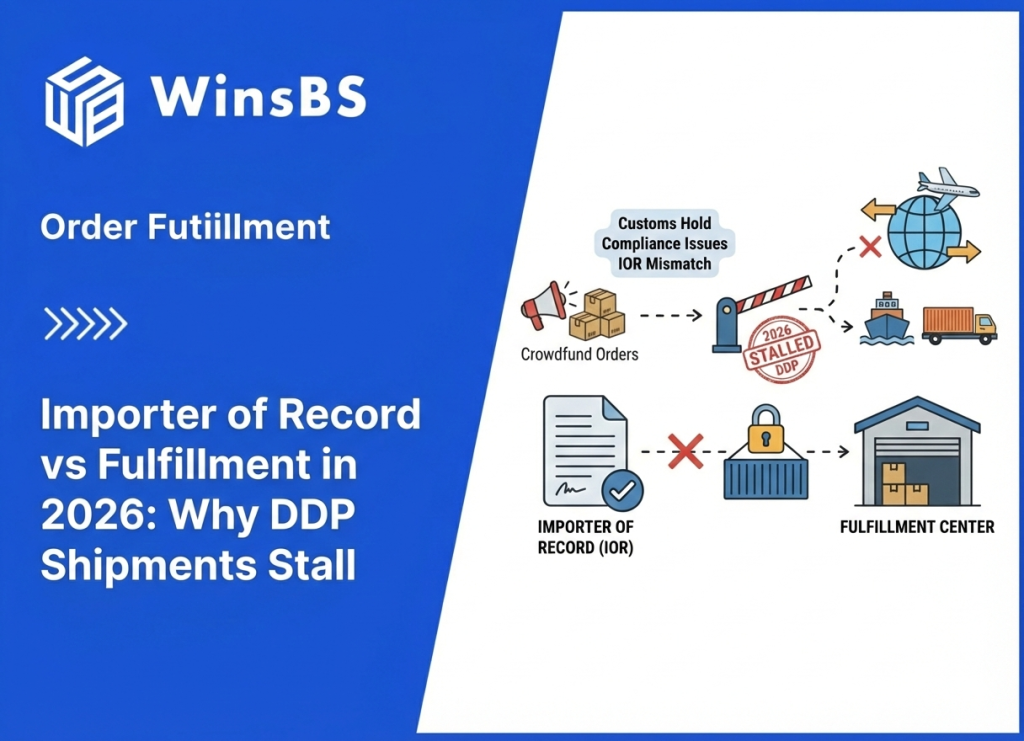

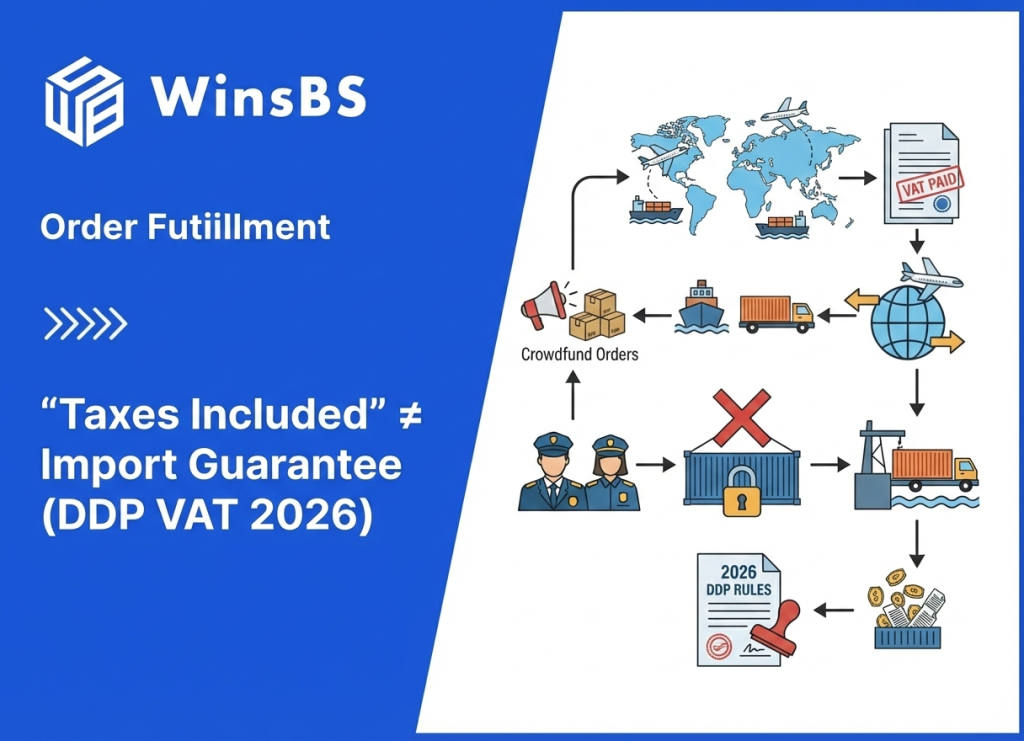

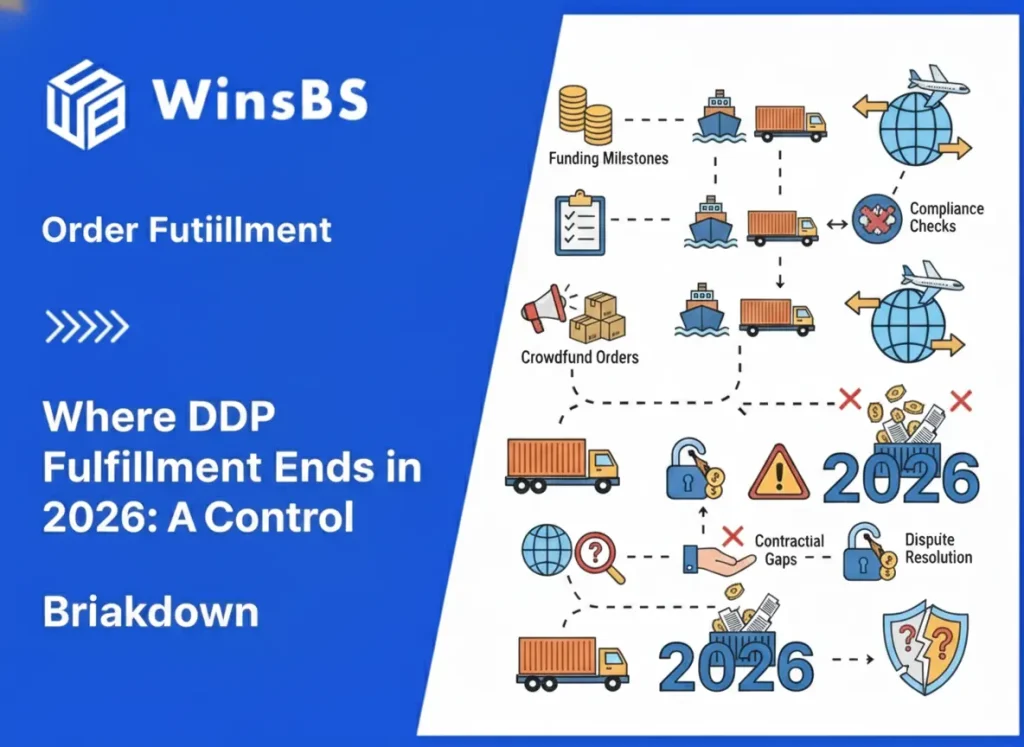

When Inventory Exists but Delivery Is Impossible in 2026 Why “In Stock” Doesn’t Always Mean “Deliverable” in Cross-Border Fulfillment WinsBS Fulfillment — Maxwell Anderson Updated February 2026 · Cross-Border Fulfillment · DDP Shipping · Customs Clearance · Inventory Availability TL;DR: In 2026, many ecommerce sellers are facing a new reality: inventory can show in stock inside the warehouse, yet the shipment is blocked at the border. This often appears as a customs hold despite inventory availability or a DDP shipment blocked at border 2026. The reason is structural. Warehouse systems confirm physical availability. Customs clearance and carrier routing systems confirm legal admissibility and route eligibility. Since the Section 321 de minimis ended impact on ecommerce shipments in August 2025, more parcels now move through formal entry review in the United States. In the EU, the upcoming €3 customs duty on low value parcels (effective July 1, 2026) adds another validation layer. In Canada, full enforcement of CARM importer responsibility increases entry-level scrutiny. If you have not reviewed where warehouse control ends, see what fulfillment actually includes in 2026 . On this page 0. The Inventory Is Available. The Shipment Isn’t Moving. 1. Inventory Exists in One System — Delivery Is Decided in Another 2. The Three Status Layers: Physical, Legal, and Route 3. Why the Warehouse Cannot Fix a Customs or DDP Block 4. Same Inventory, Different Market — Different Customs Outcome 5. When Inventory Actually Becomes Deliverable in 2026 6. The Moment “In Stock” Stops Being the Right Question Methodology & Sources 0. The Inventory Is Available. The Shipment Isn’t Moving. You log into your fulfillment dashboard and see available inventory. Units were received, scanned, and stored correctly. Nothing is backordered. Nothing is out of stock. An order is placed. It moves through pick and pack. A shipping label is generated. Tracking activates. From an operational standpoint, the order has been fulfilled under your cross-border fulfillment workflow. Then the tracking status changes. Clearance delay Held at customs Importer information required Entry under review Undeliverable — return to sender At this stage, inventory is still accurate. The warehouse shows no processing error. DDP shipping may have been selected. Duties may have been prepaid. Yet the shipment is not moving. This is the scenario behind many searches such as “in stock but cannot deliver” or “customs hold despite inventory.” Sellers are discovering that inventory availability does not guarantee customs clearance once a parcel enters formal entry review. “In stock” is a warehouse status. “Deliverable” is determined later — at customs entry and route validation. The warehouse confirms possession. Customs authorities and carriers confirm permission. 1. Inventory Exists in One System — Delivery Is Decided in Another Most ecommerce operators assume that once inventory is available inside a fulfillment warehouse, delivery becomes a matter of transportation timing. If the warehouse can pick it and the carrier can scan it, shipment completion feels inevitable. That assumption increasingly breaks down in 2026. A warehouse management system (WMS) tracks physical control: units received, units stored, units allocated, and units shipped. It verifies inventory accuracy and confirms operational execution. Customs clearance systems evaluate something different: declared value, classification, importer identity, and compliance triggers. Carrier systems evaluate route eligibility, service-level compatibility, and automated risk flags. These systems do not share a single definition of “ready.” The warehouse defines ready as physically available. Customs defines ready as legally admissible. Carriers define ready as route-compatible. This structural separation became more visible after the Section 321 de minimis ended impact on ecommerce shipments in August 2025. As more U.S.-bound parcels shifted into formal entry, customs hold rates increased — even when inventory was correctly processed and DDP shipping was selected. If you want a deeper breakdown of where warehouse responsibility ends, review what fulfillment actually includes in 2026 . When sellers search for “why shipment stuck at customs 2026,” they are often encountering this separation between physical inventory status and entry-level validation systems. 2. The Three Status Layers: Physical, Legal, and Route To make “in stock but cannot deliver” situations predictable, separate the shipment into three statuses that operate independently in cross-border fulfillment: the warehouse status, the customs clearance status, and the carrier route status. The first is physical status. This is what your fulfillment warehouse and WMS can prove: units exist, were received, and can be picked, packed, and shipped. This is the layer that shows inventory availability. The second is legal status. This becomes visible at customs entry. Even when DDP shipping is selected, customs clearance can pause if the entry record requires validation of importer identity, classification, valuation, or other admissibility triggers. This is where “customs hold despite in stock” happens. The third is route status. Carriers apply route eligibility and service-level screening. A shipment can be physically shipped and still become undeliverable if the chosen route or service level is not permitted for that shipment profile. Physical availability does not guarantee customs clearance. Customs clearance does not guarantee route eligibility. Inventory vs Deliverability: Physical, Legal, Route Layers (2026) Diagram showing that inventory availability is confirmed by the warehouse, while deliverability depends on customs clearance and carrier route eligibility. PHYSICAL STATUS Fulfillment Warehouse / WMS • Inventory received & counted • “In stock” / available quantity • Pick / pack / label executed • Parcel tendered to carrier handoff LEGAL STATUS Customs Entry / Clearance • Importer identity validation • Classification / valuation review • Admissibility triggers • Holds can occur even under DDP release ROUTE Carrier Validation • Service-level rules • Route eligibility • Automated exceptions • “Undeliverable” Inventory availability lives in the warehouse layer — deliverability is decided by customs clearance and route eligibility. The three layers that create “customs hold despite in stock” outcomes: warehouse inventory availability, customs legal admissibility, and carrier route eligibility. Once you can name these three statuses, most “DDP shipment blocked at border 2026” cases stop looking random. The warehouse can be correct and complete, while customs clearance or carrier routing is still unresolved. 3. Why the Warehouse Cannot